This story was originally published online at blackvoicenews.com.

With California’s growing population of adults aged 65 and older, challenges regarding how the state will supply care for more than six million aging adults continue to rise.

As the caregiving industry struggles to meet the demands of the aging population, many individuals find themselves taking on the role of unpaid family caregiver due to the mounting cost of care or placement. Although California has taken steps to support low-income aging adults with their care needs through programs like In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) through Medi-Cal (California’s Medicaid health program) or Medicare, for many aging adults who don’t meet the criteria for these programs, access to care is costly.

“The demographics are shifting towards people growing older, living longer. And without having an adequate long-term care system, we don’t have a lot of options for people that don’t qualify for state help,” explained Yasmin Peled, director of California Government Affairs at Justice in Aging.

To qualify for no-cost Medi-Cal, eligible beneficiaries 65 years old and older must have an income at 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) or below, which is just over $1,700 per month for one person.

For older adults with income levels that exceed Medi-Cal eligibility, they may be eligible for Medi-Cal with a share of cost, which means they would pay a fee, sort of like a deductible payment, or could potentially qualify for IHSS with a share of cost.

But oftentimes, family members and friends bear the weight of caring for their aging loved ones.

“So, that’s where the burden really falls on family caregivers at the end of the day, because that’s the only option that people have if they can’t afford care, or people go to a nursing home or assisted living and they pay down all of their income to become eligible for Medi-Cal in order to cover those services,” Peled said.

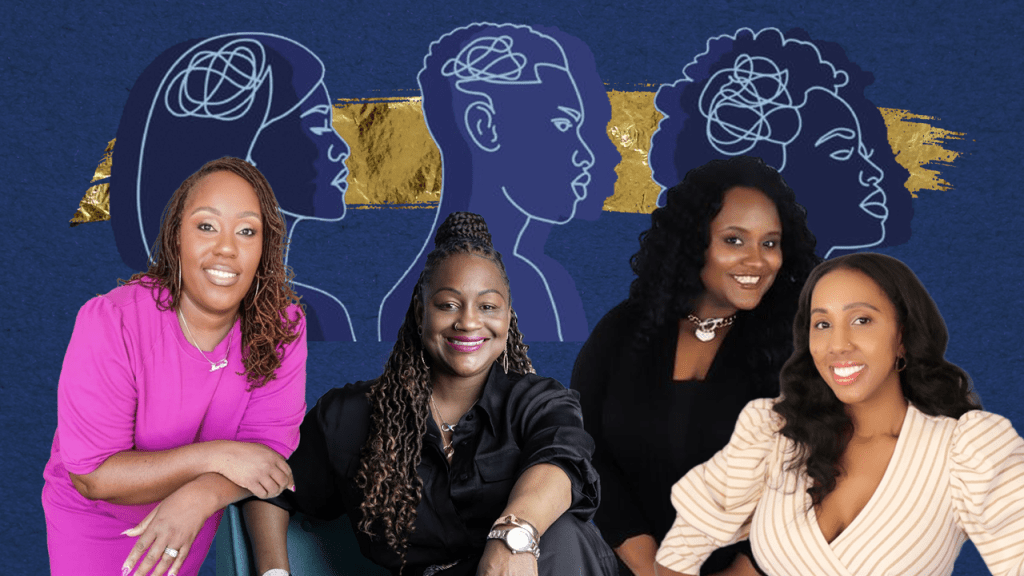

Daughters of sick and aging parents like Mrs. Jamie Cubit, Sallé Kirby and Sanja Billue each made the decision to become family caregivers , taking on the emotional, mental and financial cost of doing so. Husband and son Rudy Barbee manages the care of three of his loved ones.

Relative caregivers often shoulder the responsibility of caring for their loved ones in one way or another, whether that’s making medical and financial decisions on behalf of their loved one, overseeing their care with little medical experience or bearing the guilt of placing their loved one in a facility.

In a state with more than six million aging adults, many family caregivers grapple with how to give their loved ones the care they need while battling the financial and emotional costs of care.

The emotional cost of caregiving

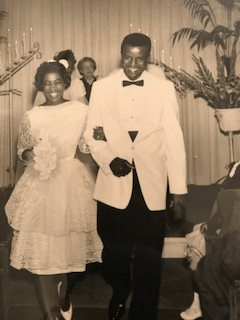

Beaumont resident Sanja Billue has been her mother’s caregiver since 2017 when her 80-year-old mother, Marian, moved in with her. Prior to that, Billue had been helping both of her parents for years. For two years Billue also took on caring for her father, John, before he passed away in June 2023.

Unlike the average family caregiver, Billue has a bachelor of science degree in nursing and has experience in the field of healthcare in pediatrics. Despite her background, Billue was unfamiliar with how much the emotional cost of caring for her parents would be.

“I have to tell you, it was a lot because they both needed a lot of care. They had a lot of appointments and stuff,” Billue said. “[My mother] was declining with her dementia. She still is. Papa had dementia as well, but he was a little better than mom was, but he was declining physically.”

Dementia is not a specific disease, but is defined as a group of symptoms such as memory loss and the impaired ability to remember, think or make decisions that impact everyday activities. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, one in five Californians over the age of 65 will develop dementia.

Although Billue cared for her parents, it took a toll on her mental health. It wasn’t until she came across the Inland Caregiver Resource Center (ICRC) did she realize there was support available to family caregivers like herself. She began taking classes on how to be a good caregiver and how to survive as a caregiver. She’s been a participant for nearly six years.

In 2023, with her father’s physical health declining and facing her own health issues, Billue had to make a decision and weigh the costs of caring for her parents and her mental and physical health.

Billue isn’t alone. A 2023 AARP study surveyed 1,001 adult caregivers and found that 50% of the participants experienced emotional stress, which was more prevalent than physical stress (37%). More female caregivers also reported feeling anxiety and stress more than male caregivers.

Billue attended a class about placing a loved one in a facility, taught by Tanya Brown, a family consultant at ICRC. Billue learned a lot about how to determine when to place a loved one and how to choose the right facility.

“We encourage all of our caregivers to take the placement class, not to tell you to place, but to provide you with the information so that if the time ever came that it was necessary for you to place, you are fully informed,” Brown said.

After taking the class, Billue and her siblings made the decision to place their dad in a nursing home with financial support from Medicaid and Medicare.

“That was really hard. But at that point, it was about saving my life. I didn’t want to die from being so stressed out,” Billue explained. Like many family caregivers, Billue was her father’s primary caregiver.

Medicare covers the cost of a skilled nursing facility for conditions that started with a hospital stay and require ongoing care once an individual is discharged, but the cost is only covered for a limited amount of time. Medicare covers all the costs for the first 20 days. From day 21 through 100, Medicare covers most of the cost, but a daily copayment is owed. After 100 days, Medicare will not cover any costs for a skilled nursing facility.

Medi-Cal will cover the cost of long-term care in a nursing home for low-income California seniors who require a nursing facility level of care and who meet the eligibility requirements. Coverage includes payment for room and board, as well as personal care assistance with activities of daily living such as getting dressed and bathing.

When he was first placed in a nursing home, Billue visited every day and asked all sorts of questions. She made sure her dad had everything he needed and that she was nice to the staff who cared for him.

“It wasn’t easy for my dad, but one day I was there at the bedside and he looked at me and he said, ‘thank you.’ I was so grateful for that,” Billue shared. “I needed those little two words because I felt guilty at times, but I didn’t want to die. And that’s where it was leading to.”

Billue has no regrets about placing her father in a facility. Learning about placement through ICRC equipped her with the information she needed to make that decision. Although caregiving is challenging and can take a toll, Billue “had to learn that I had to take care of myself.”

“The main focus of ICRC is to maintain the caregivers’ health and well being,” Brown said. “You have to have a mental health break, to have some me-time to do things that you can enjoy for yourself.”

The financial cost of caregiving

“I have two degrees and none of them are in [caregiving], but as a daughter who loved her daddy dearly, I said, ‘I’m going to take care of you, dad, and I’m going to will you back to health. So, we started our journey,” Mrs. Jamie Cubit said.

A resident of Moreno Valley, Mrs. Cubit began her caregiving journey with her father, Dr. John Washington Sr., who had a severe stroke in May 2020 that led him to rehabilitation. Her father had his first stroke in September 2019. He later had to have a heart valve replacement and underwent that procedure in January 2020.

Mrs. Cubit started caring for her mother, Mrs. Bobbie Washington, when she was diagnosed with dementia in March 2020, during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

With no experience, Mrs. Cubit took on the challenge of caring for her two elderly parents in her home. Her father received care in the home, but that care came with a $20,000 per month price tag. They paid out of pocket.

“There was no assistance. Too rich to be poor and too poor to be rich. I did not want to deplete my parents’ savings,” Mrs. Cubit said. In order to preserve their savings, Mrs. Cubit made the decision to sell their home.

According to an AARP Long-Term Care Cost Calculator , the average monthly cost of an assisted care facility in California is an estimated $5,295 per month. The estimated cost of a semi-private nursing home is $9,855 per month and $11,573 for a private nursing home. Data from the calculator estimates median costs in a region based on a national cost of care survey produced by Genworth Financial, an insurance company based in California.

The estimated cost of long-term care varies based on the type of placement. (Graphic: Chris Allen, Black Voice News)

For older adults who do not qualify for no-cost Medi-Cal because their income exceeds the 138% FPL limit, they may qualify for Medi-Cal with a share-of-cost that must be paid before Medi-Cal will pay for the rest of their covered services in that month. The share-of-cost is similar to a private insurance plan’s monthly deductible, according to DHCS.

Approximately 127,000 out of a total of roughly 15 million Medi-Cal members have a share-of-cost — that’s less than 1%.

“The problem with the program is that you have to spend down to $600 each month. You’re only allowed to maintain $600 a month for your own living expenses,” said Peled. “So, this program really puts people in financial jeopardy because you can’t live on $600 a month in California. There’s nowhere in California that you can live on that income.”

For older adults who need care, they must either “impoverish themselves” to get services or find another way to access those services, Peled stressed.

While long-term care insurance is an option for some and designed to cover a range of long-term care services typically not covered by regular insurance policies, an estimated 7.5 million — less than 4% — of U.S. adults have long-term care insurance as of 2020, according to the American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance (AALTCI). But the cost of long-term insurance varies and depends on a number of factors such as age, health status, gender, amount of coverage, among others.

Individuals who don’t qualify for Medi-Cal should consider purchasing long-term care insurance early on, according to Dr. Wessam Labib, geriatric medicine specialist at Loma Linda University. Doing so would allow long-term care insurance to supplement commercial insurance in cases where some services are not covered by a long-term insurance plans such as medical care or in-home care.

“Typically, when the patients get to the stage where they actually need help, they probably would not be successful [getting] qualified for one of those long-term care insurances,” Dr. Labib said. Without long-term care insurance, families must pay out-of-pocket for care services not covered by insurance.

Peled attributed the lack of long-term care insurance coverage among individuals to how expensive it can be to purchase the premiums. For a 65-year-old single female, a $165,000 long-term care insurance policy benefit cost $2,700 a year in 2022. Policies also increase each year based on inflation projections.

Those who are just above the Medi-Cal eligibility level have to find their own caregiving options which may be paying out-of-pocket for care like Mrs. Cubit, or recruiting a family member or friend who is often unpaid.

Caring for her parents was not easy and was a heavy weight to bear. Although Mrs. Cubit had brothers, she was the primary caregiver and didn’t receive much help from them.

“I tried to do what I could, but I was not Superwoman. I hung up my cape before our last daughter went off to college,” she said.

After much consideration, Mrs. Cubit decided to place her father and mother in a facility. Placing her parents was difficult. Mrs. Cubit received backlash from her mother’s church community after her mom told them Mrs. Cubit was selling their home.

“In the Black community, it’s ‘oh, you can’t put your parents in somewhere.’ So, it was a stereotype and a stigma that I had to overcome. And then I realized, a lot of Black people do it because they don’t have the money to put them anywhere,” she said. “That’s the long and the short of it for a lot of them. They just don’t because it is expensive.”

When Mrs. Cubit finally found a suitable facility to place her parents in, she was kind to the staff and made sure to bring candy, cakes and popcorn. She even helped with her father’s care. Though she was kind to the staff, she later found out that they weren’t kind to her parents, so she removed them.

Mrs. Cubit went on to find another facility for her parents.

The assisted living facility was “wonderful,” Mrs. Cubit noted, “but you only know what they allow you to know. You can’t be there 24/7.” Mrs. Cubit would drive to the residential facility at 12:30 a.m. to meet the night shift staff.

Although the caregivers at the assisted living facility were pretty good by Mrs. Cubit’s standards, the “shoddy care,” management team and cost of the facility — “$10,000 a month and climbing” — led her to find another place for her parents.

The board and care facility she decided to move her parents to was recommended to her by a healthcare professional who cared for her dad. Again, this was not an easy decision for Mrs. Cubit.

Board and care facilities are residential homes that have been licensed by the California Department of Social Services (CDSS) to house and provide non-medical care for elderly residents.

“I felt very guilty for a minute, but I leaned on my faith, and God let me know, ‘it’s not your battle.’ And it wasn’t. I couldn’t do it all. I wasn’t trying to do it all,” Mrs. Cubit explained.

Although she made the decision to move them into the facility, she “practically lived at the facility, which kind of defeated the purpose.”

Despite the challenges and initial guilt she felt, Mrs. Cubit has no regrets about the decisions she made on behalf of her parents. Her father would not have lived as long as he did without the care of those facilities, she acknowledged.

The mental cost of caregiving

Rudy Barbee’s first step into the role of caregiver began 11 years ago after he found his mother, Doristine, on the floor of her kitchen experiencing an intracranial hemorrhage in May of 2013, days before Mother’s Day. She was two feet away from her LifeAlert device on the counter.

That year, Barbee spent Mother’s Day with his wife and mother-in-law at a restaurant down the hill from the Intensive Care Unit of UCLA’s hospital where his mother was admitted. Her intracranial hemorrhage left her with vascular dementia, a condition that affects memory, thinking and behavior, and is the second most common type of dementia after Alzheimer’s disease .

In 2018, Barbee took on caring for his 101-year-old mother-in-law after noticing some symptoms of cognitive decline like stumbling and repeating herself. She was eventually diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and went to live with Barbee and his wife within the year. His mother-in-law currently receives supportive care from a nonfamilial caregiver during the day.

In 2021, Barbee began caring for his wife, 72, when she developed autoimmune disorders which include inflammation of her muscles (myositis), nerve damage (neuropathy) and osteoarthritis symptoms that affect her joints. With infusions and other treatment methods, his wife is able to perform limited walking, cooking and driving.

Unexpectedly thrusted into the role of primary family caregiver, Barbee began to oversee the care of his mother, mother-in-law and wife which meant gathering resources, finding specialized and quality formal care options and navigating a complex health care system.

“It’s also just very difficult to navigate the system of care. There are many different programs. There are many different services available to older adults with varying levels of helpfulness,” Peled explained. “But when you are in crisis, especially at the beginning of needing these care services, it can just be very hard to navigate the system. You don’t know where to start.”

Barbee sought support from ICRC where he accessed online educational training, attended support groups and received financial planning support.

Two years ago, Barbee’s mother experienced a small stroke. He knew he had to make a decision about long-term care, but his father disliked the idea of his ex-wife being placed in a facility.

“Based on neurological issues and level of care and the ambulatory needs, and the expediency under which we want good health and recovery, to what extent that looks like — we can’t do it,” Barbee told his father. He recognized that his mother needed focused and efficient care immediately, which is what he told his father and his mother’s neurosurgeons, physician therapist, occupational therapist and her caregivers.

Barbee “went shopping” for a post-stroke facility. He had a checklist: close to home (Rancho Cucamonga) or in the middle of where all of the siblings lived, and a high standard of care focused on occupational and physical therapy.

In addition to that criteria, Barbee identified different rates and costs of things, discussed affordability among the family and came to a consensus on what could be afforded. In addressing the cost of care, Barbee explained the importance of knowing what benefits, pensions, retirement funds and resources like ICRC are available.

Between 2021 and 2022, while living under one roof with his wife, mother and mother-in-law, a nurse informed Barbee that the house was too cold. He purchased another heating system and a solar-powered system. Barbee said it was the best thing to happen, but he had an $8,500 annual electric bill.

Addressing the cost of care can be difficult, especially when making decisions with other family members. When Barbee made financial decisions regarding care, he made sure to ask three initial questions: What is the need? What is the standard of care? What are the cost ranges in order to get those first two things?

“I’ve told caregivers, ‘I want to be able to walk out [of] this house and not have to worry about the care of my relative,’” Barbee recalled.

With the support of ICRC educational training and consultations, Barbee made it a point to address the importance of consistency to those caring for his loved ones, namely consistency of caregivers and consistency of the level of care he expected.

2His mother is a long-time beneficiary of Kaiser Permanente, and now benefits from their Medicare Advantage Plan, which covers hospital and medical insurance, and some benefits like prescription drugs. His mother is not eligible for Medicaid.

When he brought his mother to a meeting at Claremont Manor Care Center, he felt guilty. During the car ride to the facility, his mother reassured him.

“She goes, ‘I understand you’re doing the best you can and this is where we are.’ [She] just flat out articulated that in the car. I almost ran a red light,” Barbee explained. “But I told her I would never leave her alone and I wouldn’t let anybody mistreat her.”

Barbee has been overseeing her care with the caregivers and with medical personnel since day one. Although his mother lives at the care center, he visits her often throughout the week and still manages her medical program, both medications and preventive and managed care.

“I’d like anyone [reading] this to realize that placement is a component of your decision to manage care. It is not always this or nothing. It’s a decision,” Barbee said.

The cost of being the primary caregiver

In 2018, Sallé Kirby noticed changes in her mother, Marjorie Kirby’s, behavior. This included things like her mother no longer doing laundry and repeating herself.

Aware that her mother needed more assistance, Sallé moved from LA to her mother’s home in Desert Hot Springs to care for her. Marjorie, soon-to-be 91 years old, has vascular dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and congestive heart failure.

“When I moved out here to care for her before the dementia really kind of settled in, I said to her, ‘I think the reason why I didn’t get married or have kids is because God, the universe, knew that I was going to be caring for you because you didn’t have a husband or someone else younger to care for you,”’ Sallé said.

When her mother needed care, Sallé never hesitated to be a caregiver. Caregiving is something Sallé grew up watching her family do for one another. From the age of six to 19, Sallé lived in a multigenerational home.

“That was a normal thing. It wasn’t like, you put that person in a facility, or that’s where they were going. Not that I didn’t know. I knew that that existed. It just didn’t exist in my family,” Sallé explained.

While Sallé has accessed respite care from ICRC when she needed it, she didn’t realize how many other resources were available to her. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Sallé attended workshops and meetings that allowed her to learn more about her mother’s dementia. ICRC provides a four-week class called “It Takes Two,” which teaches family caregivers new skills and tools about caring for loved ones with Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias.

Sallé has been navigating the healthcare industry, but has struggled with getting her mother access to medical necessities and working with nurses from a local home health agency. As a Medicare recipient, her mother has health coverage under an health maintenance organization (HMO) insurance plan, she has been receiving home health care since being bed-bound.

Marjorie has been bed-bound since January 2024, leading her to develop a wound. She receives access to home health care which allows nurses to come in and treat the wound and bathe her, but it’s not as consistent as Sallé would like because the staff is often different people each time.

“You don’t have that consistency. And with dementia patients, when they have consistency, then their comfortability is easier. They’re not having trauma,” Sallé explained. “It helps me and it helps my mom, because it’s also where I develop a relationship with them to where we’re working as a team that makes it fit.”

As different nurses come into her home and leave notes for one another about their visits, Sallé shared that the quality of care and behavior from staff have been inadequate. As Marjorie’s primary caregiver, Sallé often asks questions about treatment plans, including if her mother can regularly access wound care and about documentation.

Over the last few months, nursing staff from the agency have characterized Sallé as difficult. Sallé noted that since June 10, 2024, she has experienced an acceleration of “inappropriate” treatment toward her and Marjorie from the home health agency. After Sallé told nursing staff she didn’t feel comfortable administering an antibiotic injection into Marjorie, they documented this as a “refusal.”

The process of administering the antibiotics involves inserting a catheter into the upper arm and injecting the antibiotics and making sure the catheter is inserted correctly. While a family member can be taught how to administer it, home health nurses are supposed to administer it if a family member is unable.

“I have said to them I don’t feel comfortable because I’m watching them do it, and they’re talking about there’s good blood flow…,” Sallé explained. “That’s not something else I can add to my list of things to do.”

During one visit with a male nurse, Sallé felt scared when he began verbally attacking her while administering Marjorie’s antibiotic treatment. Sallé called a friend to stay on the phone with her while the nurse was there. Sallé has been diligent in monitoring her mother’s medical orders and discharge paperwork. When Sallé asked a question about the nurse’s process, he informed Sallé that the agency was “documenting her behavior.”

After voicing her complaints with the home health agency, they started sending two nurses to the home — “that’s intimidating,” Sallé said. Although Sallé has asked her mother’s social worker for recommendations for other home health agencies, under Marjorie’s HMO insurance, her plan only contracts with this one agency.

While Marjorie doesn’t have to pay a copay, accessing services isn’t easy. With her plan, most of her needs must be approved with a referral by the HMO.

“I’m trying to get a specialized wound care company to service my mother. At the moment, it seems like I can’t unless it’s approved by the HMO, and the HMO may not approve it because they don’t contract with that [company],” Sallé explained.

Sallé is facing these challenges alone as her mother’s primary family caregiver. As a family consultant for 11 years at ICRC , Brown said in her experience, caregiving usually falls on one family member, even among those who have siblings.

According to a 2024 Wells Fargo report on eldercare, women made up 59% of unpaid caregivers between 2021 and 2022. As California’s population grows older and becomes larger, more and more caregivers are needed, while at the same time, family caregivers are demanding improved quality of care among care agencies and staff.

“This is the norm. It seems like when I talk to other caregivers, they’re having the same issues; nurses coming in and not knowing what to do, and you having to instruct them on what to do,” Sallé said.

ICRC is one of 11 nonprofit California Caregiver Resources Centers that serve and support family caregivers of adults affected by certain health conditions. By providing caregivers and their families with resources such as educational workshops, respite care, family mediation, support groups and referrals.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly identified the initial assisted living facility where Mrs. Cubit’s parents stayed as a board and care facility. The recommendation for the board and care came from a healthcare professional of her father. A previous version incorrectly stated that Mrs. Cubit’s father had his first stroke in September 1997. It was September 2019.